Source: https://www.chappatte.com/en/images/a-turn-for-the-worse-in-ukraine

DISCLAIMER: AS PART OF THE COURSE “STUDYING CRISIS: CONFLICT, DISASTER, AND THE SOCIAL” AT WAGENINGEN UNIVERSITY, GROUPS OF STUDENTS PREPARED PRESENTATIONS ABOUT SOME OF THE RIPPLE EFFECTS OF THE WAR OVER UKRAINE, ONE YEAR INTO IT. THIS BLOG SHOWS SOME OF THEIR FINDINGS, BASED ON LITERATURE RESEARCH, WHICH WERE PRESENTED DURING AN INTERNAL, CLOSING SEMINAR. WE SHARE IT AS AN EXAMPLE OF HOW OUR STUDENTS ENGAGE WITH REAL LIFE CRISES.

Recap Current Crisis Studio 2023: Falling out over Ukraine – Back to the Future?

26 April 2023

A year into the invasion, “Ukraine” questions our understanding of what war is, how it works, and how it engages regions and populations across the globe. The war over Ukraine manifests itself way beyond the frontline itself, in many distinct places and spaces. In this year’s Current Crisis Studio – as part of the course Studying Crisis- we zoom in on these broader manifestations of the war.

If one thing becomes clear from this episode of the Crisis Studio, it is that there are many ways to zoom in on the Russian-Ukrainian crisis context, to single out some aspect to try and understand it, and to see how these different parts add up. All four presentations contributed to disentangling some aspect of the Russian invasion in Ukraine, and hopefully – always interesting for academics – led to new questions and suggestions for further enquiry. We enjoyed the process that we started in the first week, and that over a short time materialized in four different perspectives that were presented during our final session

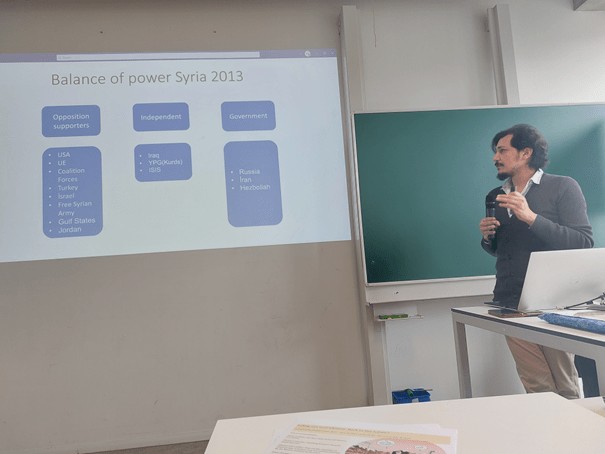

The first presentation compared the Ukrainian case with Syria and explored how the Russian military intervention in Syria led to geopolitical groupings and proxy war dynamics that although different, can also be seen as related to the Ukraine case. It asked: many conflicts, one war? And discussed if and how proxy war dynamics in Ukraine could be related to the earlier stand-offs over Syria. What the case of Syria showed is that over time the relations as part of these proxy war dynamics changed and local, regional and geopolitical configurations were altered as the conflict changed and took shape. The Russian entry into the war on the Assad side was a significant event in this regard, and showed that Russia, perhaps against western expectations, was able to maintain and sustain support for and by its military adventures abroad, but also affected local reconfigurations, for instance concerning Turkish and Kurdish factions. It may indeed be seen as a dry run for the Ukraine invasion, that made use of tried efforts such as aerial campaigns, mercenaries and ways around geopolitical protest and sanctions. The presentation brought out the dazzling complexity of geo-political relations and suggested how Cold War positionings are both reproduced and changed in each “round” of conflict.

The second group organized a round table conversation called Crisis Room as a role play, in which a variety of experts went over the politics and role of NATO in the contemporary conflict: Ukraine’s invasion: Unveiling Europe’s Security Shock Doctrine. Represented were fictitious delegates from the college of human rights; the Humboldt University in Berlin; the Transnational institute in Amsterdam, and the International Peace Research Institute in Stockholm, with a special guest from the Naomi Klein institute. The engaging discussion brought to the fore different perspectives on the apparent renewed significance and urgency of NATO. Apparent, because the mechanisms behind this significance were also criticised and analysed, among others by referring to the Shock Doctrine as a way to instrumentalise crisis to push through political ideas and programs otherwise deemed impossible or improbable, i.e., the sharp military budget increases in Germany and other countries. The militarization of Europe can be seen as subjected to such dynamics. The roundtable ended with a plea for ways around a military reflex by suggesting a Feminist Foreign Policy. How that would work in the midst of military aggression and without counter deterrence might indeed need some alternative imagination. That was what this presentation, somewhat boldly, suggested, that it is possible to imagine alternatives.

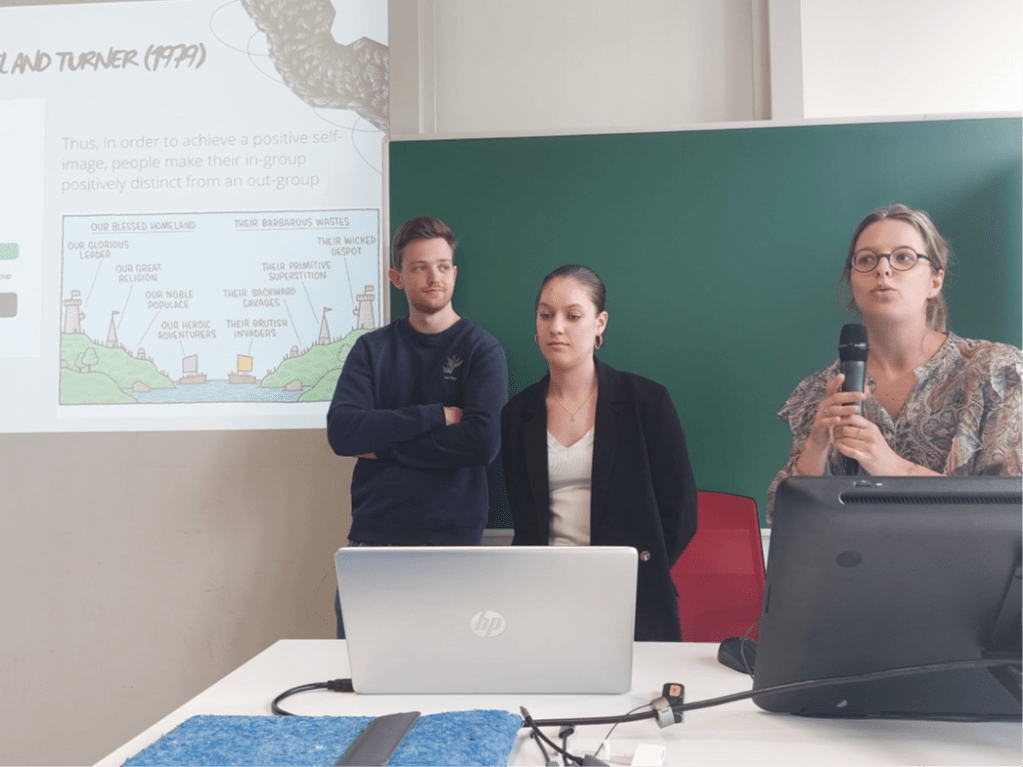

The third presentation worked around two ethnic hotbeds, namely Kosovo and Transnistria, both of which saw a re-awakening of identity claims with the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The presentation: Identity and conflict: How are the identities of ethnic groups in Kosovo and Transnistria affected by the Russian invasion in Ukraine? started with an explanation of social identity theory and ‘othering’ to introduce identity politics and the ways it gets weaponized. The presentation analyzed for the two different cases how leaders, stories, and symbols brought ethnic identities back at the core of struggle over territory and autonomy. Interesting indeed is how in the Kosovo claim, there was large support from western powers for independence, and ultimately a military intervention sustaining this. The case of Transnistria may not be that dissimilar, yet goes largely without western support and instead is

perceived as a Russian aggression. The presentation raises an interesting (and as yet unfinished) discussion that is at the heart of the study of violent conflict: Does identity bread war? Or does war breed identity?

The fourth presentation dealt with the environmental concerns brought about by war. Green Bombing- Outsmarting ChatGTP, started with an cunning quest to use Chat GPT to inquire about green bombing. It was indeed outsmarted, and it turns out that the link between environmental concerns and conventional war is quite a specific area of expertise that is broken down in different angles. Indeed, the use of bombs and military equipment on the scale of the Russo-Ukraine war destroys ecosystems, leads to a rise in Co2 emissions, and affects natural landscapes in many other ways. What the presentation built up to is the question whether it would make sense to suggest a greening of the war effort, and if a conflict such as the present one, necessitates this. Ethical dilemmas abound, and the group showed how real suggestions are actually made to make such as effort. Green bombs thus exist, or almost. This presentation wrapped up the crisis studio exercise with a novel way to bridge conflict studies with environmental concerns, or indeed making some headway into a political ecology lens to armed conflict, very fitting for a groups such as SDC. During the session we suggested that this might be an interesting avenue for a research project, let us repeat this here. Then again, all presentations showed interesting insights and room for possible research or further inquiry.

So, what have we learnt about how war works in our day and age? By and large, what these four presentations did, was showing in different ways how conflicts, interventions, but also imaginaries for remedies, are rooted in longer trajectories across time and space. Historical legacies inform ethnic identities and political alliances on different scales. Institutional arrangements are formed around these identities, and are in turn shaped by them – indeed NATO could be seen as one of those also, capturing a ‘western’ identity. Efforts to make sense of what is happening today reproduce discourses and mental schemes of the past- and there is a risk that this traps our imagination for what might be possible. That is not to say that nothing changes, it always does, but tracing how the past informs the present, or how the present is taunted by the past, clearly makes sense in the case of the war as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine: in that sense, albeit perhaps less so for the case of green bombing, it is indeed essential to go Back to the Future for Studying Crises, to link, mix, expand, and then to wake up in the present to imagine a brighter day.

Thanks for your participation and input!

Gemma van der Haar and Bram Jansen